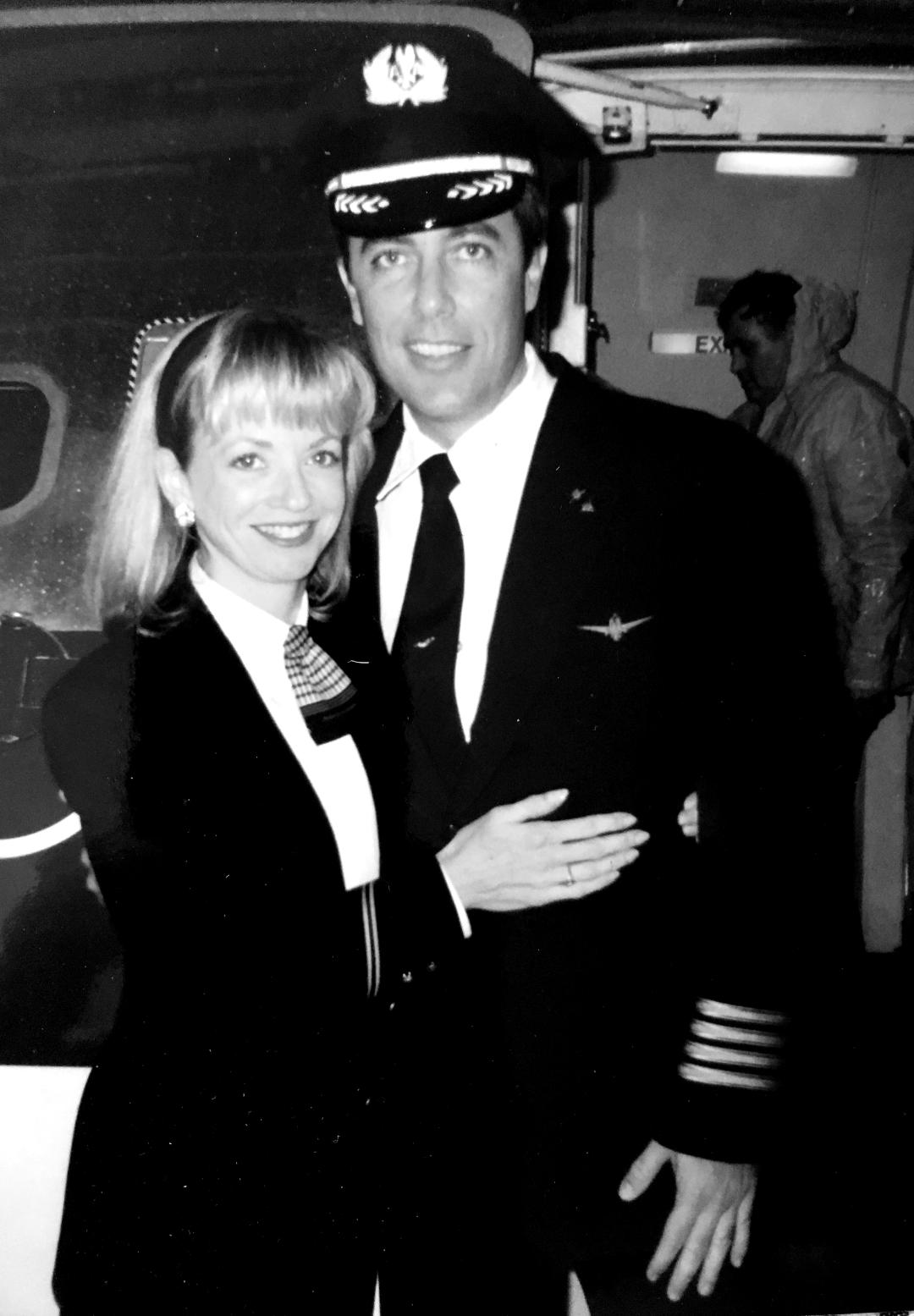

I flew the American Airlines’ MD-80s for over 20 years and more than 10,000 pilot hours. She was the mainstay of our fleet for a long time and generally speaking, it was a decent jet to fly.

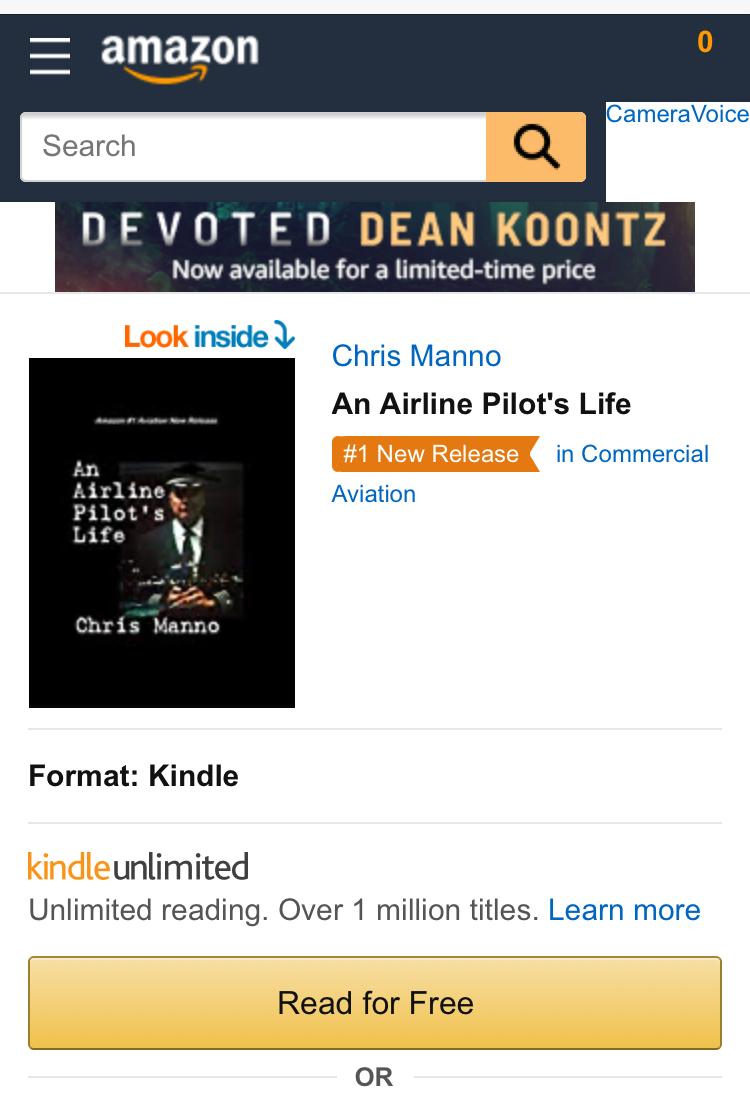

My first actual flight as copilot is recorded in detail below. This is an excerpt from my true-life story, An Airline Pilot’s Life, which is holding at Amazon’s #1 New Release in commercial aviation. In this book I take you along in the cockpits of American Airlines’ DC-10s, MD-80s, F-100s and Boeing 737s. Every training program, every aircraft shakedown flight, and more, including my years as an instructor/evaluator pilot. How do the jet’s controls feel? What are the maneuvering characteristics? How is the engine response? Get firsthand, first-person answers.

Here’s a sample, letting you sit in the copilot’s seat on my first landing in the MD-80, with 142 passengers on board:

____________________________________________________________________________________

“Localizer capture,” said Charles Clack, a Check Airman, from the left seat. Ahead, the lights of the Los Angeles basin sprawled like diamonds scattered across the blanket of night as we sank lower on our approach to Long Beach Airport.

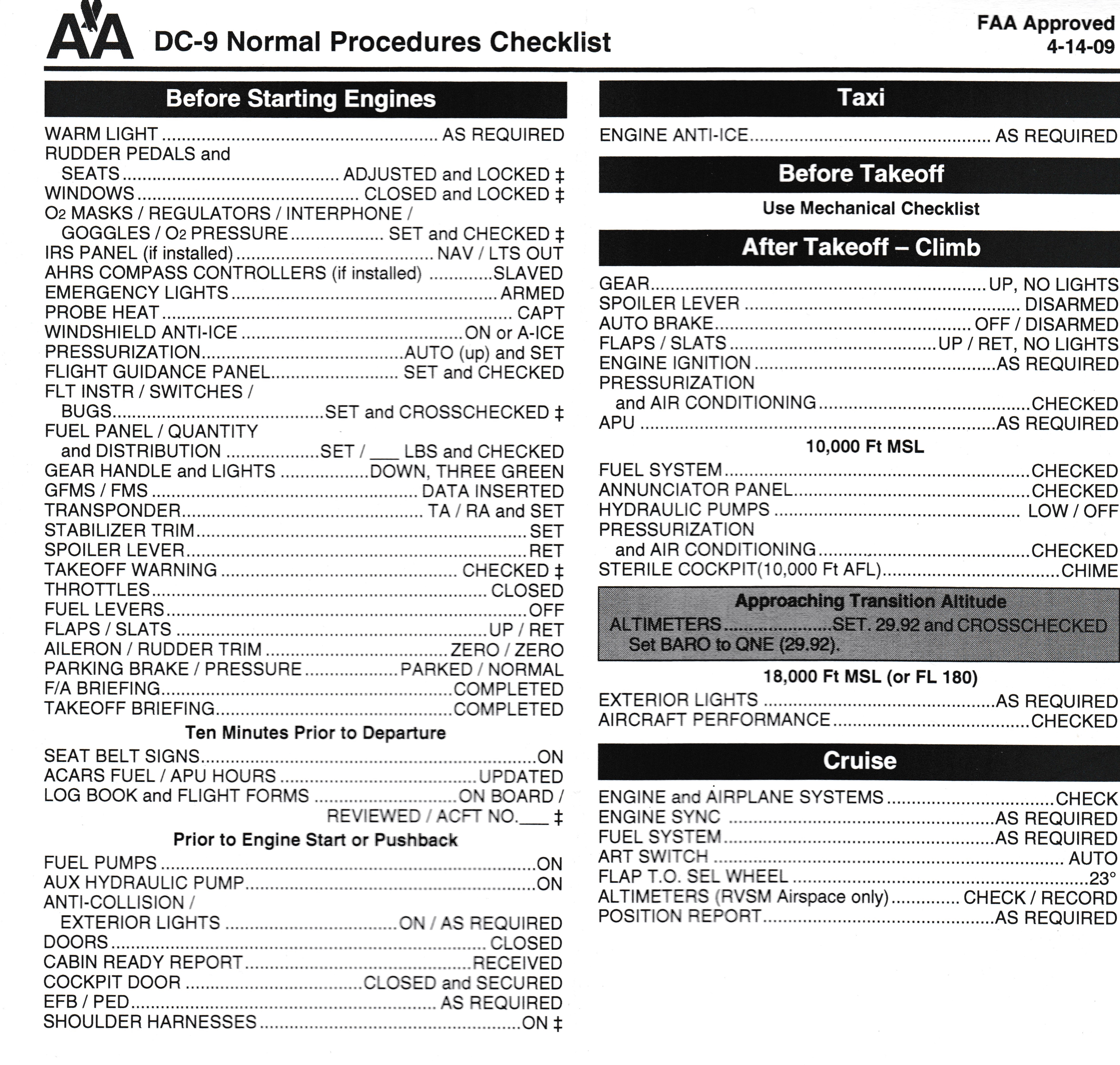

Technically, I should have made that callout, being the pilot flying, as soon as our flight director system captured the navigational signal leading us to the runway. But that was why there was a Check Airman in the captain’s seat supervising my first landing—with 142 unknowing passengers aboard—in the MD-80.

As is typically the case, I discovered the real aircraft flew better and different from the simulator, which had been my total experience “flying” the MD-80 up to that point. I had the jet trimmed up nicely and the winds were mild so she flew a steady, true course with little correction from me.

But the most important, exciting and rewarding point for me was, I was the pilot flying. That felt good, after almost two years sitting sideways at the DC-10 engineer’s panel. That had been an easy, decent gig, but this is what I was here for.

Fully configured with full flaps, the MD-80 autothrottles kept the EPR (Engine Pressure Ratio, pronounced “EEP-er”) fairly high, which was good: she flew more stable at a higher power setting with more drag. The MD-80 Operating Manual recommended flaps 28 for routine use because it saved fuel due to the reduced drag compared to flaps 40. But I learned from experience that the jet flew a better, tighter approach at the higher power setting and really, how much extra fuel was being burned from the final approach fix to touchdown anyway?

Fully configured with gear and flaps, I simply flew the long silver jet down the guy wire Major Wingo had told me about, from our vector altitude all the way to touchdown on the comparatively short Long Beach runway. The landing was firm but decent, although the nosewheel came down harder than I’d anticipated.

“I should have reminded you about that,” Charles said later in the hotel van. “With flaps forty, the nose is heavy; so you have to ease it down.”

Still, nothing could dampen my elation at having flown my first takeoff and landing in a passenger jet at a major airline. With a full load of passengers on board. That was it—I was really an airline pilot at last. Cross another item off the dream come true list, I said to myself silently.

The first officer upgrade at the Schoolhouse had been a breeze for a couple reasons. First, the McDonnell-Douglas systems logic and flight guidance processes were much the same as those on the DC-10. I already understood “CLMP,” “IAS,” “VS” and all of the flight guidance modes and what they’d do because I’d been monitoring the DC-10 pilots’ processes and procedures for a couple years.

And, I was paired with Brian, a very smart, capable captain-upgrade pilot for the entire ground school and simulator programs. He was a Chicago-based pilot, quiet, serious, and very capable. He offered easygoing help and coaching, just as he’d do with his copilots up at O’Hare and I learned a lot from him. He’d be an excellent captain, I could already tell, and in fact, he became a Check Airman himself eventually.

The MD-80 itself was a study in design contradictions. When Douglas Aircraft stretched the old DC-9 by adding two fuselage extensions, one forward of the wing root and one aft, they didn’t enlarge or beef up the wing at all. By contrast, when Boeing extended the 737 series, they’d enlarged and improved the wing. The MD-80 simply had higher wing loading, which is not an optimal situation from a pilot’s view. The lift was adequate, but certainly not ample, reducing the stall margin. While Boeing’s philosophy was “make new,” Douglas seemed to be simply “make do.”

The ailerons were unpowered, relying on the exact same sluggish flying tabs the old KC-135 tankers had. She was lethargic and clumsy in the roll axis and the actual control wheels in the cockpit were cartoonishly large to give pilots more leverage against the lethargic ailerons. To boost roll response at slower speeds, the wing spoilers were metered to the ailerons, which was a mixed blessing: they didn’t raise the left wing to reinforce a right turn; rather, they dropped the right wing with drag. In an engine failure situation, the last thing you needed was spoiler drag added to engine thrust loss in any maneuver. That was Douglas doing “make do,” as they had done with so many hastily added components on the DC-10.

The instrument panel was chaotic, as if they’d just thrown in all the indicators and instruments they could think of and then slammed the door. That left the pilots to constantly sort out useful information and block out distracting nuisance warnings. Douglas made a stab at lightening the scan load on the pilots with an elaborate array of aural warnings, a voice known as “Bitching Betty” to pilots. They just weren’t sensitive enough to be useful, like yelling “landing gear” in certain situations where landing gear wasn’t needed, which gradually desensitized a pilot to the point where you’d reflexively screen out the distraction, which was good, but also the warning, which was bad.

The most unbelievable bit of cockpit clumsiness was the HSI, or “Horizontal Situation Indicator,” the primary compass-driven course and heading indicator before each pilot. Mine on the copilot’s side was placed off-center and mostly behind the bulky control yoke. It was actually angled slightly to make it more visible to the captain, because his instrument display was also obstructed by his control yoke, an incredibly clumsy arrangement.

The ultimate design goofiness was the standby compass, which on most aircraft was located right above the glareshield between the pilots. Douglas engineers must have had a field day designing the MD-80 whiskey compass, locating it on the aft cockpit bulkhead above the copilot’s right shoulder. To use it, you had to flip up a folding mirror on the glareshield itself, aim and find the compass behind both pilots’ backs, then try to fly while referencing the compass in the tiny mirror.

The fuselage was long and thin, earning the jet the nickname “the Long Beach sewer pipe” because it had been built in Long Beach at the McDonnell-Douglas plant. Flight attendants called it the “Barbie Dream Jet” because it was almost toy-like compared to the other American Airlines narrow body jet, the 727.

The problem with the increased fuselage length was that Douglas hadn’t enlarged the rudder at all on the stretched MD-80, so the rudder itself was fairly useless for heading changes or turn coordination. All it seemed to do was torque the fuselage and have little effect on the aircraft’s azimuth. Eventually, an MD-80 pilot learned to ignore the rudder pedals in the air, unless it was needed to control yaw during a thrust loss on either engine.

The aspect of having the engines mounted along the aircraft centerline was a good deal compared to wing mounted engines which incur more asymmetrical yaw in an engine failure and I appreciated that. The engines were so far back that you couldn’t hear an engine failure in the cockpit, so there were actually warning lights to alert pilots of a failure.

The JT8D engine response was forceful and the engines themselves were the Pratt and Whitney equivalent of the gutsy General Electric TF-33 fanjets we had on the EC-135 J at Hickam. Minus the roll heaviness and disregarding the cockpit design mess, I wasn’t about to let anything dampen my enthusiasm for line flying as a pilot at a major airline.

I’d waited long enough to bid first officer that I could actually hold a set schedule rather than an “on call” reserve pilot schedule. At my seniority range, the trips weren’t very good, but they were trips just the same.

My first month I held a schedule of early two day Buffalo trips. Still, I was undaunted—I had a schedule! A regular airline pilot trip.

________________________________________________________________________________

Read more: fly the DC-10, the F-100 and more.

Get your copy of An Airline Pilot’s Life in paperback or Kindle format from Amazon Books HERE. Makes a great Father’s Day gift!

Want a signed copy (US only)? Click Here.