There are many, many good reasons why you should NEVER fly into Reagan National Airport in Washington DC. And I’ll tell you why you shouldn’t, and I mean fly–not sit on your butt in the back of the plane. Of course, it goes without saying that if pilots shouldn’t fly there, neither should passengers. And here’s why.

1. The Postage Stamp Effect: like LaGuardia in NYC, the airport was built in the early days of commercial aviation, when the defining factors in aircraft design were slow air speeds, light weights, agile propeller aircraft. Fine.

Maneuvering this thick-winged, lumbering prop job on final was routine at a relative crawl compared to today’s heavier swept wing jets, which need lots of room in the air and on the ground to operate safely. But Washington National is a postage-stamp sized airport from a bygone era, and the serpentine “approach” hasn’t changed:

Look closely at the approach and notice the approach course–145 degrees, right? The runway heading is 194, so do the math: there’s an almost 50 degree heading change on final–and look at where that occurs. It’s at 424 feet above the ground. Which brings up my next point:

2. Extraordinary low-altitude maneuvering: The wingspan of the 737-800 is over 130 feet long, and the jet is normally sinking at a rate of 700 feet per minute on short final. Thirty degrees of bank at 400 feet with seconds to touchdown, with each wingtip dipping up to 50′ in a turn less than 200′ above the ground? And while a 20 degree offset is considered a challenge, the final alignment on such a typical offset approach happens early–but this turn is after the minimum descent altitude, and you get to finalize the crosswind correction at the last second landing on a marginally adequate runway length:

Look at the runway length of the “long” runway: that’s right, 6,800 feet–200′ shorter than LaGuardia’s aircraft carrier deck, and often on final approach, the tower will ask you to sidestep to the 5,200 foot runway instead. So before you even start the approach, you’d better figure and memorize your gross weight and stopping distance corrected for wind and in most cases, you’ll note that the total is within a couple hundred feet of the shorter runway’s length.

Then figure in the winds and the runway condition (wet? look at the numbers: fuggeddabout it) So the answer is usually “unable”–but at least half of the time I hear even full-sized (not just commuter sized) jets accepting the clearance. I accepted the clearance (had a small stopping distance margin and the long runway was closed for repairs) to transition visually to the short runway one night and at 500 feet, that seat-of-the-pants feel that says get the hell out of town took over and I diverted to Dulles instead.

“Do you fell lucky today, punk?”

If that wasn’t hairy enough (get the pun? “hairy,” “Harry?”) from the north, approaching from the south, you’ll also get the hairpin turns induced because they need more spacing to allow a take-off. Either way you get last second close-in maneuvering that would at any other airport induce you to abandon the approach–but that’s just standard at Washington Reagan. And once you’re on the ground, stopping is key because there’s no overrun: you’re in the drink on both ends. Is the runway ever wet when they say it’s dry? Icy when they say “braking action good?”

And with the inherent challenges at the capitol’s flagship airport, you’d expect topnotch navaids, wouldn’t you? Well not only do they not have runway centerline lights or visual approach slope indicators (VASI) from the south, plenty of the equipment that is installed doesn’t work on any given day. Here’s the airport’s automated arrival information for Thursday night:

Just a couple things to add to the experience, right?

So let’s review. If you’re flying into Reagan–and I’ve been doing it all month–to stay out of the headlines and the lagoon, calculate those landing distances conservatively. The airport tries to sell the added advantage of a “porous friction overlay” on the short runway that multiplies the normal coefficient of friction, but accept zero tailwind (and “light and variable” is a tailwind) and if there’s not at least 700 feet to spare–I’m going to Dulles (several deplaning passengers actually cursed at me for diverting) without even considering reentering the Potomac Approach traffic mix for a second try at National.

Think through the last minute alignment maneuver and never mind what the tower says the winds are, go to school on the drift that’s skewing your track over the river and compensate early: better to roll out on final inside the intercept angle (right of course) because from outside (left of course) there’s no safe way to realign because of the excessive offset and low altitude. A rudder kick will drag the nose back to the left inside the offset, but from too far left, you’re screwed.

Once you’ve landed, now you face reason number 3:

3: The northbound departure procedure. Noise abatement in places like Orange County-John Wayne are insanity off of a short runway with steep climb angles and drastic power cuts for noise sensitive areas. But DCA has an even better driving forces: the runway is aimed at the national mall which is strictly prohibited airspace.

Again, no problem in a lumbering prop job–but serious maneuvering is required in a 160,000 pound jet crossing the departure end at nearly 200 mph: the prohibited airspace starts 1.9 miles from the end of the runway. We’re usually configured at a high degree of flaps (5-15 versus the normal 1) so you’re climbing steeply as it is–in order to prevent violating the prohibited airspace, you must maintain the minimum maneuvering speed which means the nose is pitched abnormally high–then you must use maximum bank to turn left 45 degrees at only 400 feet above the ground.

What do you think will happen with the nose high and the left wing low if you take a bird or two in that engine? Are there any waterfowl in the bird sanctuary surrounding the airport? Would the situation be any different with a normal climb angle with wings straight and level?

What do you think will happen with the nose high and the left wing low if you take a bird or two in that engine? Are there any waterfowl in the bird sanctuary surrounding the airport? Would the situation be any different with a normal climb angle with wings straight and level?

So what’s the payoff for this complicated, difficult operation?

It’s a nice terminal. Congressmen like their free parking at National. And they’re way too busy to ride the Metro to Dulles, despite the bazillion dollars appropriated to extend the metro line from the Capitol to Dulles, adding another twenty minutes to the airport travel time is too much for our very sensitive congressmen to endure.

I think that’s about it as far as pluses and minuses. Fair trade, considering all the factors?

That’s for you to decide for yourself, but hang on–we’re going anyway. Just don’t chew my ass when I land the jet at Dulles instead of Washington Reagan National. Because for all of the above reasons, you probably shouldn’t have been going there anyway.

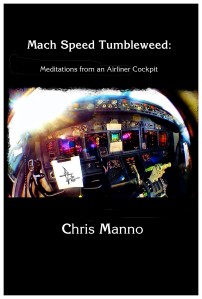

More insider info? Step into the cockpit:

These 25 short essays in the best tradition of JetHead put YOU in the cockpit and at the controls of the jet.

Some you’ve read here, many have yet to appear and the last essay, unpublished and several years in the writing, I consider to be my best writing effort yet.

Own a piece of JetHead, from Amazon Books and also on Kindle.

Ditto for a go-around or windshear options: the MD-80 is famous for it’s slow acceleration–I’ve been there MANY times–and when you’re escaping from windshear or terrain, I can promise you the pucker factor of the “one, Mississippi, two Mississippi” on up to six to eight seconds will have your butt chewing up the seat cushion like horse’s lips. Not sure if that’s due to the neanderthal 1970’s vintage hydro-mechanical fuel control (reliably simple–but painstakingly slow to spool) or the natural limitation of so many rotor stages. But the 737’s solid state EICAS computers reading seventy-teen parameters and trimming the CFMs accordingly seem to give the performance a clear edge. And a fistful of 737-800 throttles beats the same deal on the Maddog, period. Advantage, Boeing.

Ditto for a go-around or windshear options: the MD-80 is famous for it’s slow acceleration–I’ve been there MANY times–and when you’re escaping from windshear or terrain, I can promise you the pucker factor of the “one, Mississippi, two Mississippi” on up to six to eight seconds will have your butt chewing up the seat cushion like horse’s lips. Not sure if that’s due to the neanderthal 1970’s vintage hydro-mechanical fuel control (reliably simple–but painstakingly slow to spool) or the natural limitation of so many rotor stages. But the 737’s solid state EICAS computers reading seventy-teen parameters and trimming the CFMs accordingly seem to give the performance a clear edge. And a fistful of 737-800 throttles beats the same deal on the Maddog, period. Advantage, Boeing.

Which got me to thinking. There are a lot of good reasons why I couldn’t be an airline pilot either. Here they are:

Which got me to thinking. There are a lot of good reasons why I couldn’t be an airline pilot either. Here they are: “Get over here,” he’d growl, and you were busted. “This will only take forty minutes and you can go do whatever afterward.” Never forty, maybe four hours and forty minutes, then your day was shot. Dammit. So I’d be the reluctant tool lackey as Dad hunkered waist deep in the yawning engine compartment on the Chevy 396 with a four-barrel carb that with the air filter off, looked like a toilet flushing the way it guzzled gas (that was cool) even at idle.

“Get over here,” he’d growl, and you were busted. “This will only take forty minutes and you can go do whatever afterward.” Never forty, maybe four hours and forty minutes, then your day was shot. Dammit. So I’d be the reluctant tool lackey as Dad hunkered waist deep in the yawning engine compartment on the Chevy 396 with a four-barrel carb that with the air filter off, looked like a toilet flushing the way it guzzled gas (that was cool) even at idle. But I fly with a lot of guys who like my dad have wiring diagrams, flow charts, Lamm schematics–they like to get under the hood, yacking with the mechanics. “Shows 28 volt three-phase; now if you lose one phase . . .” blah blah blah is all I’m hearing. Just let me know when it’s fixed. Unlike my dad, they don’t want me handing them wrenches and like his Chevy Caprice, I don’t want to know how it works or even why it works–just let me know when it’s working again. I can fly the hell out of it for sure but the rest is all just details eating up my afternoon. Fix it, I’ll fly it, end of story.

But I fly with a lot of guys who like my dad have wiring diagrams, flow charts, Lamm schematics–they like to get under the hood, yacking with the mechanics. “Shows 28 volt three-phase; now if you lose one phase . . .” blah blah blah is all I’m hearing. Just let me know when it’s fixed. Unlike my dad, they don’t want me handing them wrenches and like his Chevy Caprice, I don’t want to know how it works or even why it works–just let me know when it’s working again. I can fly the hell out of it for sure but the rest is all just details eating up my afternoon. Fix it, I’ll fly it, end of story.

Somebody else is going to have to do the playacting for the public; I’m not good answering questions about the bathroom, yucking it up about flying, or hearing about how (this is standard) “we dropped a thousand feet straight down” on some other flight. Doing the pilot thing as a pilot in the air–that is my only concern. Don’t worry about a thing, it’s taken care of–just keep your seat belt fastened and like Lewis CK says, “You watch a movie, take a dump and you’re in LA.” Just don’t expect a show before or after.

Somebody else is going to have to do the playacting for the public; I’m not good answering questions about the bathroom, yucking it up about flying, or hearing about how (this is standard) “we dropped a thousand feet straight down” on some other flight. Doing the pilot thing as a pilot in the air–that is my only concern. Don’t worry about a thing, it’s taken care of–just keep your seat belt fastened and like Lewis CK says, “You watch a movie, take a dump and you’re in LA.” Just don’t expect a show before or after. This is actually a sticker on sale at the Crew Outfitters store at DFW Airport. Which means some douchebag pilot thought it was a “cute idea,” (what the hell is “giggity giggity?”) and enough are actually buying the sticker to make it worthwhile. Wonder why I want to be invisible?

This is actually a sticker on sale at the Crew Outfitters store at DFW Airport. Which means some douchebag pilot thought it was a “cute idea,” (what the hell is “giggity giggity?”) and enough are actually buying the sticker to make it worthwhile. Wonder why I want to be invisible?

Like the author’s life, the story is an unlikely, relentlessly driven paradox of impossible factors that leaves the reader exhausted but fulfilled, terrorized while simultaneously enchanted, disgusted yet amused and ultimately, completely amazed. Mullane the aviator reminds me of a similarly high octane squadron mate of mine who went full-throttle against all obstacles. He’d demonstrate his wrath at even the normal delay associated with crossing a runway by doing so when cleared with a kick of afterburner.

Like the author’s life, the story is an unlikely, relentlessly driven paradox of impossible factors that leaves the reader exhausted but fulfilled, terrorized while simultaneously enchanted, disgusted yet amused and ultimately, completely amazed. Mullane the aviator reminds me of a similarly high octane squadron mate of mine who went full-throttle against all obstacles. He’d demonstrate his wrath at even the normal delay associated with crossing a runway by doing so when cleared with a kick of afterburner.

Sure, there are some flimsy walls partitioning off this mess–and your mess–from the general public. And believe me, they ARE flimsy walls too–weight is fuel burn which is cost in flight. But shrewd aircraft designers rely on the ambient background noise of flight (you know: jet engines, 300 mile and an hour wind noise) to cover up your bodily noises on the can, much like the lame exhaust fan in a tiny apartment is intended as background noise so you can crank away without disgusting a cohabitant. Lesson for the wise: don’t do anything in an aircraft lav on the ground that you don’t want others to hear. Because they will, especially as they troop past on boarding, and they’ll give you that look when you step out.

Sure, there are some flimsy walls partitioning off this mess–and your mess–from the general public. And believe me, they ARE flimsy walls too–weight is fuel burn which is cost in flight. But shrewd aircraft designers rely on the ambient background noise of flight (you know: jet engines, 300 mile and an hour wind noise) to cover up your bodily noises on the can, much like the lame exhaust fan in a tiny apartment is intended as background noise so you can crank away without disgusting a cohabitant. Lesson for the wise: don’t do anything in an aircraft lav on the ground that you don’t want others to hear. Because they will, especially as they troop past on boarding, and they’ll give you that look when you step out. Being confused with this:

Being confused with this:

But again, it’s as outdated as the prop job in the drawing above, never mind the natty dress and Pepsodent grins. Because besides the issue of today’s cramped lav (space is $, remember), there’s the detail of sanitation: it’s as clean as your average outhouse, and often smells like one. Because either you have the swirling tank of port-o-john water below, or on more modern jets, no water at all–just a non-stick coating with fragrant skid marks anyway:

But again, it’s as outdated as the prop job in the drawing above, never mind the natty dress and Pepsodent grins. Because besides the issue of today’s cramped lav (space is $, remember), there’s the detail of sanitation: it’s as clean as your average outhouse, and often smells like one. Because either you have the swirling tank of port-o-john water below, or on more modern jets, no water at all–just a non-stick coating with fragrant skid marks anyway: So anyone who says they have joined “The Mile High Club” is either A) Lying, B) Disgusting, or C) Has lost the will to live. And here’s the dirt on option “C:” there is no supplemental oxygen in the lav.

So anyone who says they have joined “The Mile High Club” is either A) Lying, B) Disgusting, or C) Has lost the will to live. And here’s the dirt on option “C:” there is no supplemental oxygen in the lav.

In all probability, you’re meeting your maker like Elvis’s last public appearance: face down, pants down, toilet unflushed. Now that’s the stuff of legends, right?

In all probability, you’re meeting your maker like Elvis’s last public appearance: face down, pants down, toilet unflushed. Now that’s the stuff of legends, right? At least you’ll be able to breathe no matter what demonstration of disgustingly poor judgment you’re finding necessary to pursue in the can.

At least you’ll be able to breathe no matter what demonstration of disgustingly poor judgment you’re finding necessary to pursue in the can.

Yes, that’s a blanket of snow down there, and uncommon October dumping of thick, wet flakes wreaking havoc on the surface: fall foliage still on the trees gathers the fat flakes in a blanket that snaps branches and snags power lines.

Yes, that’s a blanket of snow down there, and uncommon October dumping of thick, wet flakes wreaking havoc on the surface: fall foliage still on the trees gathers the fat flakes in a blanket that snaps branches and snags power lines. Our flight 9409 from Miami checks in on frequency, entering a holding pattern. “We have the Miami Dolphins on board,” the pilot says, pleading with New York Center, “Anything you can do to get us into any of the New York airports would be appreciated.” Must be coming up to play either the Giants or the Jets.

Our flight 9409 from Miami checks in on frequency, entering a holding pattern. “We have the Miami Dolphins on board,” the pilot says, pleading with New York Center, “Anything you can do to get us into any of the New York airports would be appreciated.” Must be coming up to play either the Giants or the Jets. Now that’s funny: starting to see holding? We’re in a holding pattern. But there’s the bad news: JFK is landing south which conflicts with the LaGarbage traffic pattern landing north. Crap.

Now that’s funny: starting to see holding? We’re in a holding pattern. But there’s the bad news: JFK is landing south which conflicts with the LaGarbage traffic pattern landing north. Crap. “I can get you Boston or LaGuardia, eventually,” says the air traffic controller to our Dolphins team charter. “Standby,” comes the tense answer, and I know why.

“I can get you Boston or LaGuardia, eventually,” says the air traffic controller to our Dolphins team charter. “Standby,” comes the tense answer, and I know why.

Jill calls from the back again: “Our lady on oxygen just passed out again. The number four flight attendant is also a nurse, says she’s probably having some blood sugar problems.”

Jill calls from the back again: “Our lady on oxygen just passed out again. The number four flight attendant is also a nurse, says she’s probably having some blood sugar problems.” “Tell ’em the braking action is good,” I tell the F/O as we start running the after landing checklist. That’ll help the next guys in for planning purposes. Now all we have to do is park, turn around, and fight our way back into the air through de-ice and crappy runway problems.

“Tell ’em the braking action is good,” I tell the F/O as we start running the after landing checklist. That’ll help the next guys in for planning purposes. Now all we have to do is park, turn around, and fight our way back into the air through de-ice and crappy runway problems.

To demonstrate the veracity of this story, here are my qualifications: none. I’d tell you I’ve flown thousands of times, but the truth is; I haven’t. I’ve sat in the back…and done nothing… (Usually F, but “the back,” nonetheless) while someone else has flown me thousands of times. A certified ass-sitter. I’d offer the 60 some hours of single-engine piston time I have, though that’s also irrelevant when you’re sitting in 25C, and the “I’m a private pilot and I KNEW something was wrong” doesn’t fly either, pun intended. Or worse yet, I recently heard someone feign importance with that disgusting sentence, but referred to himself as a “GA-VFR pilot.” Go ahead; tell the FAA you’d like “one general aviation-visual flight rules, to go please”. Incredible.

To demonstrate the veracity of this story, here are my qualifications: none. I’d tell you I’ve flown thousands of times, but the truth is; I haven’t. I’ve sat in the back…and done nothing… (Usually F, but “the back,” nonetheless) while someone else has flown me thousands of times. A certified ass-sitter. I’d offer the 60 some hours of single-engine piston time I have, though that’s also irrelevant when you’re sitting in 25C, and the “I’m a private pilot and I KNEW something was wrong” doesn’t fly either, pun intended. Or worse yet, I recently heard someone feign importance with that disgusting sentence, but referred to himself as a “GA-VFR pilot.” Go ahead; tell the FAA you’d like “one general aviation-visual flight rules, to go please”. Incredible.