Ask an Airline Pilot: Why Do I Feel So Worn Out After a Flight?

This is a question that I get asked by the most astute travelers: why do I feel physically worn out after a routine flight?

That’s a very good question, born of savvy observation among those passengers who fly often. And they’re right: flying has a direct physical impact on your body for very clear reasons, which I’ll explain. And–good news–there are some things a passenger can do to minimize many of these effects.

The culprit with the most insidious effect is one of the most obvious factors in your flight–and also the most underestimated, and that is, ALTITUDE. I’m only talking about the aircraft’s altitude indirectly, because what really affects you as a passenger is the cabin altitude.

The controlling factor in the cabin altitude is the the hull design of the aircraft. Because the pressure at altitude is a fraction of that at sea level, the aircraft’s pressure hull must have the strength to hold survivable (for humans) pressure in an extremely low pressure environment at altitude. For the sake of structural integrity, the difference between inside and outside pressure has to be minimized and the way to do that is to allow the cabin altitude to climb with the aircraft altitude, gradually, to a higher altitude to minimize the differential pressure.

The picture above is of a pressurization gage that shows aircraft altitude, cabin altitude–and the difference between the two. The aircraft’s pressurization system gradually raises the cabin pressure with the climb to altitude to keep the differential within the aircraft hull’s design limits. The result? At 41,000 feet, the aircraft cabin is over 8,000 feet.

That’s like being transported to Vail, Colorado (elevation, 8,000′) in a matter of twenty or thirty minutes. Suddenly, your body must make do with a significantly reduced partial pressure of oxygen, and this after being depressurized like a shaken-up soda can: every bit of moisture in your body–and gasses as well–are affected by the rapid (compared to a gradual drive from sea level to Vail) change of pressure.

This affects your body like the bulging of a balloon animal: the pressure reduced around you makes everything swell. Maybe not as dramatically as the balloon animal, but with definite and perceptible effect. And that cycle is repeated on the way down, in the opposite manner: your body must accommodate the repressurization.

Some people are more susceptible to the effects of altitude than others: I’m one who doesn’t feel well doing prolonged physical activity at altitude above 5,000 feet. I don’t like skiing or the outdoors type stuff in the mountains because of the flu-like effects of physical exertion at higher altitudes. Common side effects, or what’s called “altitude sickness,” include flu-like symptoms such as headache, body and joint pain, fatigue and a feeling of being out of breath.

If you’re the type who is susceptible to “altitude sickness” in any degree, you shouldn’t underestimate the effects of cruising for several hours at a high cabin altitude.

Next on the list of stress factors has to be humidity–or more importantly, the lack of humidity at altitude. The cabin air comes from outside at altitude where the humidity is around 1% to 2%. Fresh air is drawn in, heated, then mixed with cooler air to provide a comfortable cabin temperature. Mythbusters: I’ve heard the urban legends about “restricted air flow” to save money; recirculated rather than fresh air in airline cabins. That’s all bunk, at least in Boeing and Airbus aircraft. The cabin pressure is maintained through constant circulation and in the Boeing, large fans draw the air throughout the cabin and cargo compartments, then through the electrical compartments for cooling, then to an outflow valve for metered release with respect to a stable cabin altitude.

The pressurization and air conditioning systems work great, supplying fresh, conditioned air but . . . the humidity is very, very low because the source air at altitude is exactly that way. So, if you as a passenger aren’t drinking water constantly–you’re going to feel the effects of dehydration quickly at altitude.

The last of the major but often underestimated stress factors is also obvious but insidious: noise and vibration. Consider the basic fact that each engine on a 737 weighs over a ton and each has a core that spins at over 30,000 RPM at idle power. At cruise power, the vibration is subtle but distinct, transmitted through the airframe to everything and everyone on board.

That has a physical side effect added onto the motion effects of flight: pitch and roll changes in combinations you don’t experience on Earth. Like trains, ships and cars on a rough pavement, vibration is transmitted to your body and has a wearing, fatiguing effect.

Noise? Absolutely: there is a layered level of noise from engines, airstream outside and air flow inside that is both fatiguing and cumulatively, wearing.

What can you do about these three factors that can literally wear you out as you travel by air? Let’s start with the last factor: noise. This one has a really easy solution:

Earplugs. The foam kind, available in any hardware store. We use them in the cockpit all the time, because wind noise in the pointy end is much louder than in the back, depending on altitude and speed. They’re disposable, they’re cheap–and they work. You can still hear normal conversation just fine and the important thing is that they will reduce the fatigue level you will feel after a long flight. Try them on your next flight.

Low humidity? This is tied to the altitude effects as well, and this is a simple solution as well: hydration. Certainly on board you should be drinking plenty of water (yes, you’ll have to bring water with you–it’s available in airports everywhere; if you’re really cheap, just bring a bottle and refill it at a water fountain in the airport) but also, you need to think ahead.

Like the preparation for a marathon, you need to stay well-hydrated the day and night before the event.

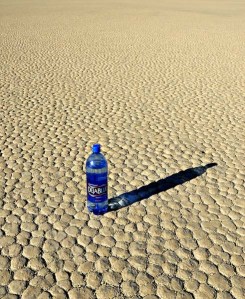

If you step on board marginally hydrated or actually slightly dehydrated, the 2% humidity at cruise altitude will outpace any attempt you make to catch up, much less keep up. Coffee? Alcohol? Diuretic soft drinks? See photo above.

Finally, the high altitude effects of cruise flight. The good news is, going forward, that the next generation aircraft like the 787 “Dreamliner” are capable of maintaining significantly lower cabin altitudes during cruise. This is very important on long flights and the fact that Boeing designers recognized this passenger stress factor and have designed a way to minimize the effects underscores my original point about the stress.

For now, though, the best you can do is to deal with the other two key stress factors–hydration and noise–and simply try to be in decent physical shape: those who are suffer less with the stress of altitude exposure.

In the final analysis, you can’t completely avoid the physical stress of air travel without avoiding air travel itself. But, if you are a savvy traveler, you can at least recognize the effects and take simple steps to minimize the effects of air travel on your body and ultimately, your trip.

Bon voyage.

September 19, 2012 at 10:21 am

Reblogged this on drndark.

September 19, 2012 at 10:28 am

Reblogged this on robert's space and commented:

because you didn’t dress warm enough or drank too little.

September 19, 2012 at 11:45 am

Hi Captain Chris!

Great post! I read something about hydrating yourself well on a flight so I did on my last one! Never really encountered jetlag and you always feel a little sluggish after an 8h + flight/sit but all went well!

The 787, I think I read that somewhere, even has better humidity so it’s getting better and better 🙂

Kind Regards,

Bas

September 19, 2012 at 2:04 pm

I didn’t know that, but a pilot friend just mentioned the humidifier on the 787 to me. I’m surprised the big long-haul cruisers like the 747 and A-380 don’t have that very important amenity already.

September 20, 2012 at 1:29 am

Is it perhaps due to concern over oxidization on internal components?

Great post and great blog by the way Chris, I can’t tell you how much I’ve enjoyed the blog and the conversations on the podcasts! Keep it up for sure and happy flying!

September 19, 2012 at 12:45 pm

timely article. I’m leaving for Texas on Friday, traveling from Ottawa and I was concerned about the long flight, cause I always feel drained after flying more than an hour. So, started drinking lots of water in preparation and I’ll bring along the ear plugs too.

I’m off to visit my beau, who is a pilot, and he didn’t tell me about this!!!

September 20, 2012 at 9:33 am

It’s true about the 787 and the humidity as well as the lower cabin altitude. Boeing uses these a big selling point to passengers, as well as larger windows.

I have taken part in some creature comfort studies at Boeing. One was for cabin noise levels, another was for turbulence. The turbulence one was fun, we rode in a full simulator and had to complete some grade school homework type tasks while the sim was shaking us around.

September 21, 2012 at 8:42 am

The grade school tasks are hard to do when the cabin is bumping around–ditto touch-screen inputs on the flight deck. Glad the 737-800 has no touch screens.

But, as my flight attendant bride reminds me, somehow coffee gets poured and not spilled in back regardless.

September 20, 2012 at 12:12 pm

As always, a nicely detailed, well-researched answer to the question. And of course the whole “balloon factor” goes double for SCUBA divers, who shouldn’t dive within 24 hours of their flight.

All the bodily effects remind me of the olden-times (early 1900’s) admonishments from physicians that said the human body wasn’t designed to endure “breakneck speeds” of over 20mph, and the stress of pressure changes when soaring above 100′ above the ground 😉

September 23, 2012 at 11:18 am

[…] https://jethead.wordpress.com/2012/09/19/ask-an-airline-pilot-why-do-i-feel-so-worn-out-after-a-flight/ […]

September 26, 2012 at 6:39 pm

Nice post. Liked the comparisons with the ballon animal and traveling to Vail….never considered the noise – but will now! As always great pix

March 17, 2014 at 2:43 pm

Imagine all of these effects on flight attendants who are up, working in this environment day after day after month after year. Been there, done that. 30 years’ worth. Yes. It really takes a BIG toll on the human body! Great article, Chris!

March 17, 2014 at 3:04 pm

I admire and respect all of the hardworking cabin crews worldwide who make air travel the safe, comfortable experience that it is.

Tough working conditions, selfless performance 99.9% of the time. I defy anyone to do their job better.

March 24, 2014 at 2:05 am

Hello Chris, .

It’s a great article that I’ll share with my friends, colleagues and relatives. This perspective of a pilot so far hasn’t been shared in any of our conversations.

I’m sure your blog post will start the discussion amongst us.

Personally though, I do take the steps to hydrate myself but I hesitate to drink lots of water as I dislike taking frequent toilet trips in the aircraft.

Cheers and all the best!

March 24, 2014 at 2:11 am

Reblogged this on Andy Querouz and commented:

Hello relatives, colleagues and friends, The blog is from the perspective of an experienced pilot. He explains the topic very well giving you some answers to some of your questions. Cheers l

September 3, 2014 at 2:06 pm

Did you know that there is a “medical” terminology for outgassing? It’s called HAFE (High Altitude Flatus Expulsion). Paul Auerbach published it in the Western Journal of Medicine.

March 15, 2015 at 1:37 am

What’s your opinion of people with COPD flying? Can they get oxygen from the airline? (Paying for it, of course.) I have a portable Inogen concentrator, but have yet to fly with it. I’d appreciate your thoughts on COPD and air travel

March 15, 2015 at 8:16 am

That’s a question that requires medical expertise I don’t have. Your doctor is the right person to discuss that with.

March 15, 2015 at 3:25 pm

Thanks, Chris. I’ve talked to my doctor(s) about flying. It’s hard to get a clear, concise answer from them. Since my portable unit only weighs about five pounds, I’m going to hop on a plane when I need to.